River Friends

Some initial reflections upon returning from canoeing the Upper Missouri Breaks "in the company and service of our ancestors"

The Peace of Wild Things

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.— A Wendell Berry poem as recited one night by Big Country, one of the three river guides who, with their cooking and hauling and shade-making and many-other-task-doing, made the FreeFlow course, Good Ancestors, possible.

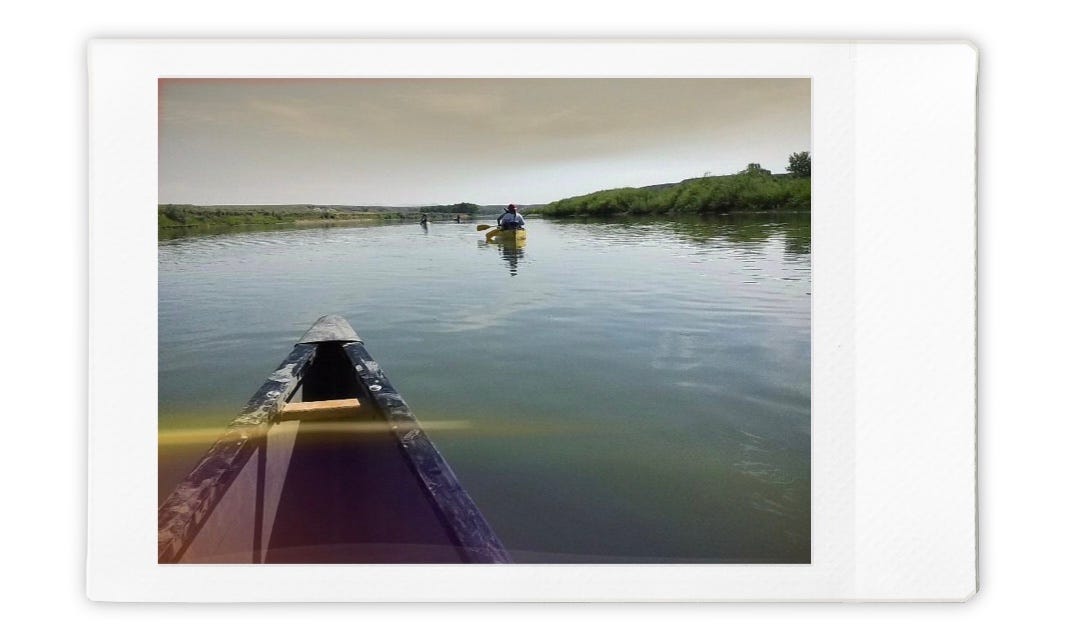

I was nervous about bringing along my Nikon so I got an Instax Mini Evo instead. Mostly, I kept it in a ziplock bag inside my drybag, but I did manage to snag a few pics as we went along. This was from the first few minutes out on the water.

What I learned about rivers from canoeing 40 miles through the Upper Missouri Breaks with Chris La Tray (writer of One-Sentence Journal: Short Poems and Essays From the World At Large and the Substack, An Irritable Métis, among other things), 8 other program participants, a FreeFlow Institute organizer, and three River Guides — writers, artists, and beautiful souls, all:

The river is alive.

The river is our relative.

Big Country said: the river is energy. If he stands in the river and his sister in Alabama stands in a river, they are connected.

G*1 said: The rivers are veins.

As Chris liked to point out, if you see an old west painting of a settlement in the middle of the plains, that painting is bullshit. Settlements were by water. You had to have water.

The river has moods.

The same river can be many colors at different times and in different places.

Don’t fight the river (unless you really have to) because the river is likely to win. L taught me that but the river *really* taught me that.

No one knows the river’s gender for sure. Z, another Good Ancestor student, tried different genders. Maybe the little wavelets on a windy day were female. Maybe the eddies — swirls formed when water flows into a void — were male. Maybe they were genderless, or their own gender. A river gender.

I woke up as soon as the sun began to rise, often when the sky was still grey through the triangular flaps at the top of my borrowed tent. I’ve never done anything like this, so almost every piece of equipment I had was borrowed: the tent, the sleeping bad, my mess kit.

If you’re enjoying WanderFinder, please do consider subscribing for free:

If you’re already a subscriber, please do pass along this copy of WanderFinder to someone who you think might enjoy it.

Like Blanche Dubois, I relied on the kindness of strangers (and friends), and strangers who turned into friends.

I hate relying on the kindness of strangers (and friends), and strangers who turned into friends.

I hate relying on anyone and then I had a lupus flare the second day out.

My left leg — the one that was paralyzed ten years ago, kicking off a long search to find the cause — swelled, probably because of the intense sun. I had brought walking sticks as a “just in case” precaution. Here was the case.

So I woke up early because I was excited and not used to sleeping outside and thrilled about the sunrise and the glorious views and also because it took me longer to get moving than anyone else. Longer to crawl from my tent and face the sun, longer to go to one knee, longer to place one hand on my water bottle and one hand on the walking stick and stand.

Once I was up, I was OK. I could go to the pit toilet, wipe down with some body wipes, take my medicine, write a little, and by that time others would be up and someone would blow the conch shell to signal that coffee was ready.

A few people had watches but I didn’t so once I turned off my cellphone, the blowing of the conch shell was the only way I had to tell time.

I think something was mentioned before the trip about cellphone service, but I thought we were going to be out of range the way I’m out of range when I drive down to see my Mom in Blacksburg, Virginia. Sometimes I go through mountain passes on that drive and the person on the other end says “what?!?” And I shout, “I THINK WE’RE LOSING THE CONNECTION! I’ll call you back!!!”

And then I wait fifteen minutes and call again and usually things are Ok.

I couldn’t imagine that in the U.S., you could travel for a week with no WiFi. I was wrong. This was the backcountry. There was nothing, not even one of those SOS signals.

My cellphone was a brick. I turned it off.

So in this system of time, the first conch shell meant coffee and a light first breakfast of granola, yogurt, and fruit if you wanted it.

Generally, during coffee time you were expected to get yourself ready and take down your tent or at least get close to having your stuff ready to go.

Hanging my wet clothes out to dry features in an oddly high percentage of my photos.

I borrowed a mallet, the other side of which could be used for pulling out tent steaks. (J and A, sisters who lived in Montana and who owned the mallet, taught me that.)

Another conch shell blast. Zoey — FreeFlow trip organizer, naturalist, logistician, birder extraordinaire, and total sweetheart — mostly took care of the morning blasts. Later in the day, she might let someone else take a turn — J, a soft-spoken art teacher, turned out to have a special conch-trumpeting talent.

Each day was slightly different, but this conch blast might let us know “circle” was starting. In a circle, we discussed our reading and writing concerning being a good ancestor, the theme of the course. How did we relate to our own ancestors? How did our ancestors relate to the land from which they came? In what ways could we be a good ancestor to our descendants, defined in the broadest possible sense?

Or, if we were going to do circle a little ways down the river, then it was time for second breakfast — a hot breakfast with and egg-and-veggie scramble maybe or pancakes or a breakfast sandwich.

And then it was time to load the boats and push off.

I tried to do most of my loading myself, but again and again, people picked up a little extra for me. L, who grew up on the rivers, might take my camping chair down with her own. When I was really in trouble, Big Country took my wet bag with all my stuff. Chris or Zoey held the boat steady for me when I got in.

Big Country helping with the boats.

The supply boat piloted by two of the river guides, Big Country plus either Ash or Jamie. The other guide canoed with us.

And then we’d paddle.

I never ended up steering — the position in the back of the canoe — but I did learn a lot about paddling from K, who used to row competitively.

Hold the paddle close to the boat, K told me. Don’t waste energy. Paddle ten strokes on one side and then ten on the other so you don’t get tired. (I always got distracted and forgot to count.)

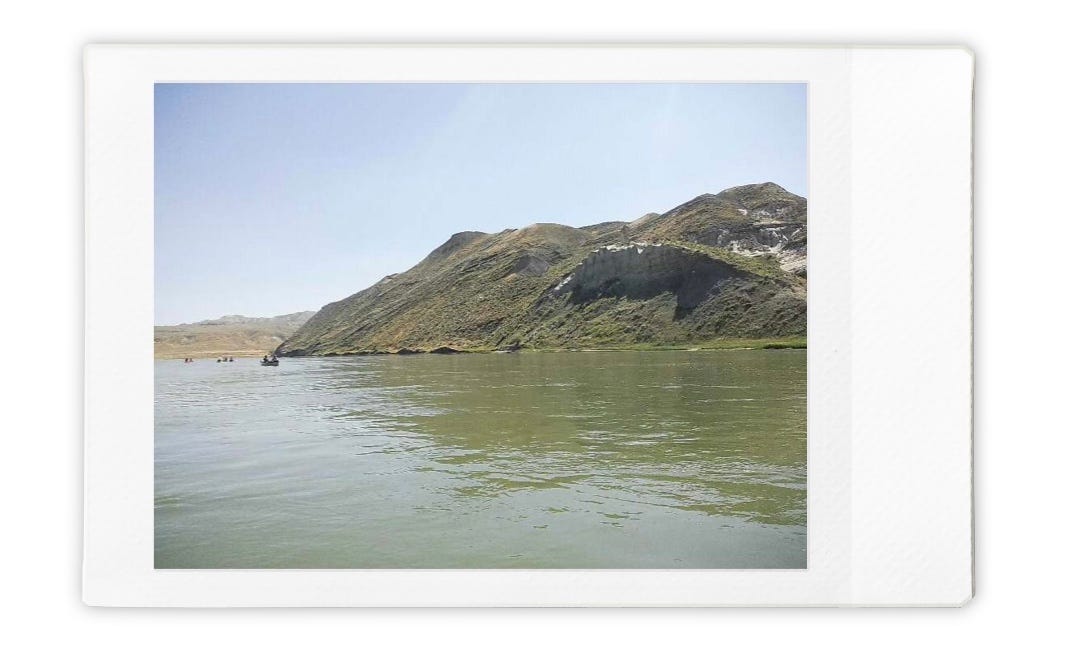

I got distracted mostly because the landscape we paddled through was ever-shifting and always astounding.

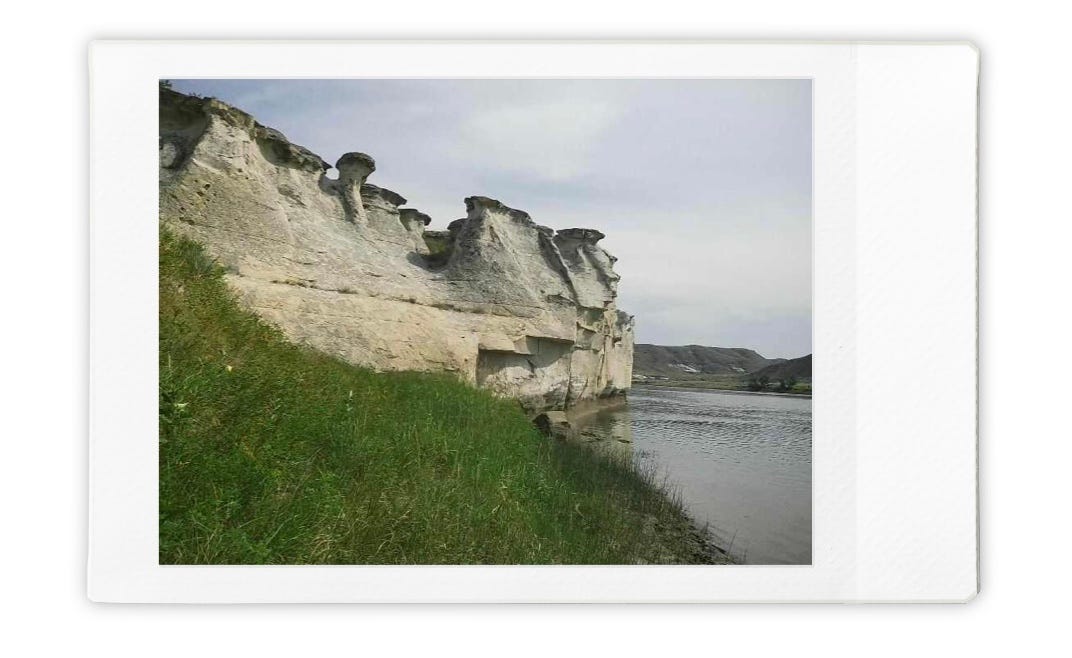

Sometimes it was sheer white cliffs shaped on top exactly like a patch of mushrooms. Cliff swallows dove in and out of tiny vase-like structures made from the mud and the swallows’ own spit.

Sometimes we canoed through sheer cliffs on either side that looked like the entrance to an Abyssinian temple except much larger and over and over again for miles.

Lord of the Rings-like. Overwhelming. The kind of landscape that feels immediately and obviously sacred.

Sometimes we canoed through high cliffs where you could clearly see the breaks that name the area — “breaks” refer to the breaks in the rocks that expose the many layers of rocks below.

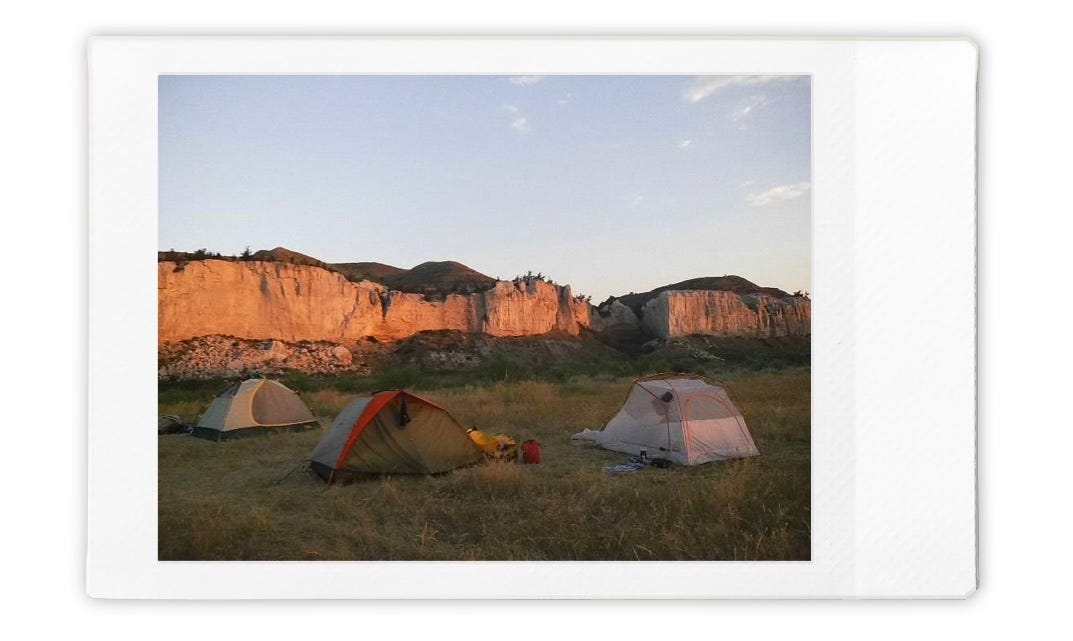

Most days we canoed 10+ miles. We camped at Coal Banks Landing, Hole in the Wall, Eagle Creek, Slaughter River. We took out at Judith Landing and went to the American Prairie, which I’ll have to describe in a future post.

In the evenings, we unloaded, set up our tents, rested, had another circle, and ate dinner prepared by the river guides. (The food was healthy & wonderful.) Someone blew the conch for each of these occasions. By sunset or even before, I was ready for bed.

After a while, I began to wonder:

What if I was not dependent on the kindness of strangers & friends, but part of a community? What if the river was also a member of my community — yes, and also the land and the rocks and the dust I sat in?

What if you are a member of my community too? What if you can stand in a river and feel the ghost of my spirit, the part of me still floating in the Upper Missouri Breaks?

I hope you can feel that peace with me. I hope you too feel that the river and the land are your ancestors.

What if we could be a good ancestor to them? What would we do now if we wanted to be a good ancestor to the land and the rivers and our communities? What if the land and the people, the river and the trees, what if we are one?

I’d love to hear your thoughts, and hope you have a wanderful week.

I’ve abbreviated the names of the other participants because it seemed like the right thing to do and also I’m not 100% sure of who said what when. Sorry folks if I got it wrong.

I led canoe trips for a couple of summers in my late teens (I know! Who would send their middle schoolers into the BWCA with a 17 year old these days?!?). Two different trips we had kids get mildly ill, one with a stomach bug, one got bit by something and his hands swelled up. Watching the other kids incorporate their reduced abilities into the trip without making a big deal about it is one of my favorite memories of those summers. As a group, the kids were responsible for getting all but 2 canoes, the packs, paddles, boat cushions etc across every portage, and we left it to them to figure out how they wanted to do it. The kid with the swollen hands was pretty strong, and couldn't paddle, but the others would flip the canoe for him, and steer from each end, and he could carry the portage.

Those summers were so formative to who I am, and how I think of community both human and more-than-human. I'm so glad you got to experience the Missouri, and the gigantic character of our world out here. Such a lovely piece -- thank you!

What a beautiful WanderFinder. I feel your spirit and the river's, as do your many readers. Thanks for letting us experience the "kindness of strangers": people, land, and river, ancestors too.

Panthea