A while ago I was reading an interview with a zookeeper and he said something like, “when the kids with down syndrome have their field days? You should come then. That’s when the zoo lights up. Lions start pacing and roaring. Polar bears go on alert.”

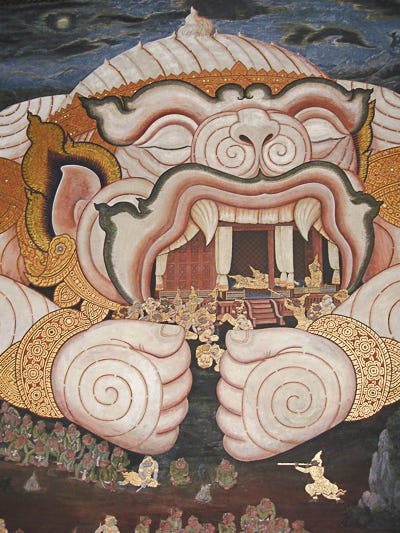

It’s stuck with me, this image of the whole zoo, watching these particular kids, hungry for them. The predators sensing, or thinking they sense, weakness or at least, difference.

For one thing, I bet the kids have a great time. I bet the kids think the zoo is always like that. For them the tiger never huddles, almost invisible on one side of his enclosure so that you have to point at his haunched shoulder and say “look! a tiger” when he so obviously wishes nothing more than that you, your family, this whole zoo, this whole city, this whole country and everything that led him to this point would get swallowed and chewed, slowly and bloodily, right in front of him, by the tiger gods.

We’re not so unlike the tigers, we immediately sense differences too.

Much is made of us as prey animals: our old-brain amygdala keeping us jumpy as a trucker on his fourth internet mail-order No Doz.

But unless you’re in a men’s rights group or vehemently anti-vegetarian, the fact that we’re also predators tends to get talked about less. Sometimes, though, I feel my front teeth, the canines, for confirmation that yes, I am a natural born hunter.

(Teenagers tend to be more fascinated by this, as the various wolf and even wolf-tooth graffiti on this sign indicates.

The sign was found on a hike with Tom Pluck, but more on that another time.)

As humans, we scan for threats, but we also scan for weaknesses, and we’re very good at spotting them.

All of us are magnificent at spotting physical differences from the norm. Even the sweetest, kindest among us will clock them. We might not do anything with the information. We might even, given the right circumstance, notice and plan to offer assistance, if it seems like assistance might be helpful. But we always notice. I don’t think we can turn it off, the noticing.

I mention all this because my rent is going up and so I need to move, and I’m lucky enough to be able to purchase a condo. The search for a new home has made me feel vulnerable, though, and it’s made me think of a lion I once met.

For readers new to this newsletter, I have lupus. For me, it manifests mainly (right now) as a neurological, skin, and connective tissue disease. Also it seems to be cosplaying a little recently as rheumatoid arthritis, so who knows? As people who have autoimmune diseases know, you rarely get one; it’s more of a Pokemon, collect-them-all kind of situation.

The point being that the things that were problems last summer canoeing down the Upper Missouri are now ***problems***. I’m fighting with my insurance to get a fix (I hope). In the meantime I often have a limp. I’m looking at condos and asking about accessibility. I’m thinking about handicapped parking.

I feel like I look weak. I worry about that, in the city.

I look like you could take advantage of me. I look like I can’t fight back. If you were a tiger or a god or perhaps even somewhat less than a god, you could put your great arm down on the sidewalk and scoop me right into your mouth.

In Kenya, on safari, I’ve never seen a kill. But I did once see an injured lion, so injured she had dug herself, or so it seemed, her own grave.

Inside her hole, her fur lay flush with the grass. I imagined a lone lawn mower coming across the endless, almost golf-like green of the Masi Mara and being able to walk over the lion without missing a beat, perhaps only nicking a little errant ear fluff.

That’s how deep she was in the womb of mother earth. She returned herself to the earth and rested and waited.

Members of her pride might have brought her food, if she wanted some. I doubt she did. Maybe she licked her wounds, occasionally.

This picture was taken with a 600mm telephoto lens. I and the group I traveled with gave her wide berth.

We didn’t think she’d live. But then, a few days later, when we returned, the hole was empty. No lion, no bones, no scrap of flesh. Gone.

She rested in the arms of the earth, then she rose again. Lazarus the lion.

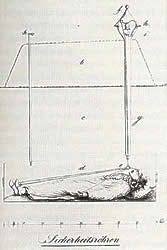

A week or so later, no longer in the Masi Mara but in the center of Kenya, our guide Philip asked my then-husband Michael and I if, after we were buried, if there was a way for the buried person to let the living people know that there had been a mistake.

He spoke from personal experience. When Philip was a young boy, he got very sick and then he died. Or so it appeared to his parents and to everyone in his community.

They held the funeral rites for him. This was not a short ceremony. It took several days. And still, it was clear to everyone that Philip was dead.

Finally, they did the last thing that you do in Philip’s community with a corpse: they moved his body outside the protective barrier of the village and left him for the wild animals to find.

The next day, his Uncle went to look for his remains. But there were none. Imagine his surprise to discover that young Philip had awaken and managed to hide all night from the predators.

I had never heard of such a thing, but Michael nodded knowingly. “It isn’t used any more I believe,” he said, “but there used to be a bell.”

A bell would be hung by the grave and a string would stretch from the bell, through the newly turned dirt, through the casket door, and the body would hold the end. If by some chance a mistake had been made and you were buried alive, you simply rang the bell.

Sometimes we are dead. But sometimes we are not. Sometimes we appear weak, but sometimes we are not. Sometimes, we just need a bit of rest, a moment of being held — suspended almost — in earth’s warm palm.

In the time it has taken me to write this essay, I have found a place to live. I love it because the men who owned it for the past 27 years loved it. The condo building is well over a hundred years old and rather than knocking everything down and covering it all in uniform black granite like some kind of bleak ice skating rink at the end of the world, these two kept little historical details: the pressed tin ceiling, the old pantry. I love it because it’s a small coop and therefore, apparently, a real community.

I love it because it seems like a place I might rest, fooling the world, fooling the monsters, possibly fooling god even, before ringing my bell, lifting myself up, ready to re-enter the city.

That’s what home is for, I think, and that’s what the earth can sometimes be for: to lie on, to gather strength from, to be cupped and cradled and held until we’re ready to go deeper or to walk once more.

And now in Blacksburg they have a space at Westview cemetery set aside for natural burials...no coffin, no chemicals. We can go back to the dust from whence we came.

This was beautiful. Sometimes we all need to dig a need to rest a while.