I have a story about oysters, and it’s also a story about violence.

Maybe most of our stories about oysters are about violence. I think they’re also about abundance. A bountiful world. Food jumping out of the sea and — easy as that — into our bellies. They open their mouths, we open our mouths, an exchange — of a kind — is made.

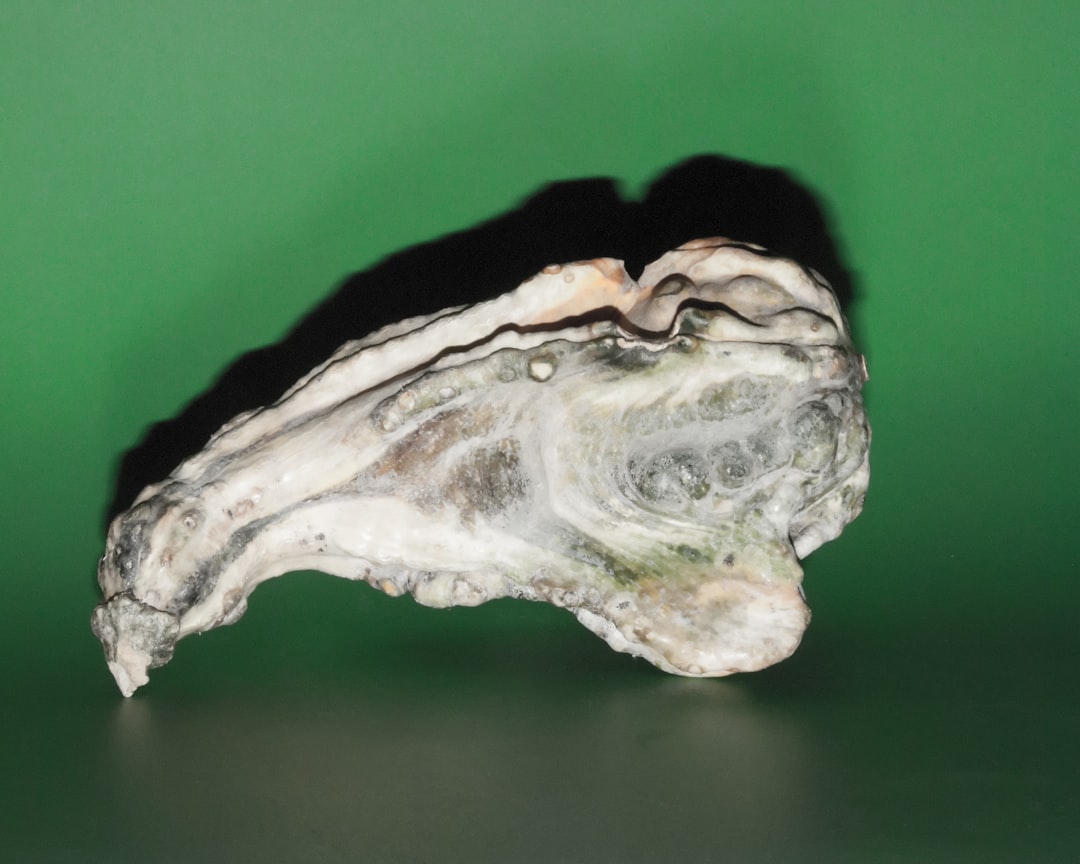

Still Life with Oysters, 1876 — Paul Gauguin

I once read Pepy’s Diary — the diary of a man in living during the plague in England in the 17th Century — and I basically took from it three things: one, that Pepys was willing to risk the actual plague in order to stay in London and continue to fuck his mistress; two, that the man basically never slept; and three, that this guy never met an oyster he couldn’t eat. I mean my god! Holy Neptune! I have no idea whether point three was at all related to points one and two but once you start reading (if you haven’t before), and if you’re not absolutely as gobsmacked by the number of oysters Pepys can consume as I was, then I would like to sponsor your entry into a competitive eating contest.

Try out this entry from November 24, 1665 for just one little instance of Pepys’ absolutely bonkers life:

Up, and after doing some business at the office, I to London, and there, in my way, at my old oyster shop in Gracious Streete, bought two barrels of my fine woman of the shop, who is alive after all the plague, which now is the first observation or inquiry we make at London concerning everybody we knew before it. So to the ’Change, where very busy with several people, and mightily glad to see the ’Change so full, and hopes of another abatement still the next week. Off the ’Change I went home with Sir G. Smith to dinner, sending for one of my barrels of oysters, which were good, though come from Colchester, where the plague hath been so much. Here a very brave dinner, though no invitation; and, Lord! to see how I am treated, that come from so mean a beginning, is matter of wonder to me. But it is God’s great mercy to me, and His blessing upon my taking pains, and being punctual in my dealings. After dinner Captain Cocke and I about some business, and then with my other barrel of oysters home to Greenwich, sent them by water to Mrs. Penington, while he and I landed, and visited Mr. Evelyn, where most excellent discourse with him; among other things he showed me a ledger of a Treasurer of the Navy, his great grandfather, just 100 years old; which I seemed mighty fond of, and he did present me with it, which I take as a great rarity; and he hopes to find me more, older than it. He also shewed us several letters of the old Lord of Leicester’s, in Queen Elizabeth’s time, under the very hand-writing of Queen Elizabeth, and Queen Mary, Queen of Scotts; and others, very venerable names. But, Lord! how poorly, methinks, they wrote in those days, and in what plain uncut paper. Thence, Cocke having sent for his coach, we to Mrs. Penington, and there sat and talked and eat our oysters with great pleasure, and so home to my lodging late and to bed.

I mean … two barrels of oysters? Did barrels mean something else in Pepys’ day? Are we talking barrels like barrels-of-wine barrels? Barrels like you-could-concievably-wear-one-and-throw-yourself-off-a-waterfall — that kind of barrel? I never really got an answer for this, how big the barrels were in Pepys’ time. Even if the barrels were smaller, it still seems like a lot of oysters.

But then again, isn’t that what we want from our oysters? A profusion? An oyster bar, with an endless display on ice? A seafood tower?

And it’s not just us in relatively modern times who eats a lot of them, wants a lot of them. We’ve got such a long history with oysters and other seafood, we can date ourselves using our leftover piles of their remnants. Shell middens — ancient piles of discarded shells — change the soil’s acidity, which tends to preserve whatever else is left in them. They’re complicated to excavate — think of it, the enormous pile of chipped and broken shells, maybe one for each home, maybe at a central town dump. Big feasts, big celebrations, or just snacks, family meals — and after each of them, a deposit is made, an addition to the teetering stack, layered between bits of pottery, scraps of leftovers.

These days, most oysters that we eat are farmed, but I’m guessing that the oysters my cousin brought from France were wild, fresh caught. Anthony Bourdain has a story about those sorts of French oysters — the first oysters he ever ate — in his book, Kitchen Confidential:

Monsiuer Saint Jour (the oyster fisher), on hearing this – as if challenging his American passengers – inquired in his thick Girondais accent, if any of us would care to try an oyster. My parents hesitated. I doubt they’d realized they might actually have to eat one of the raw, slimy things we were currently floating over. My little brother recoiled in horror. But I, in the proudest moment of my young life, stood up smartly, grinning with defiance, and volunteered to be the first. And in that unforgettably sweet moment of my personal history, that moment still more alive for me than so many of the other ‘firsts’ which followed – first pussy, first joint, first day in high school, first published book, or any other thing – I attained glory. Monsieur Saint-Jour beckoned me over to the gunwale, where he leaned over, reached down until his head nearly disappeared underwater, and emerged holding a single silt-encrusted oyster, huge and irregularly shaped, in his rough, claw like fist. With a snubby, rust covered oyster knife, he popped the thing open and handed it to me, everyone watching now, my little brother shrinking away from this glistening, vaguely sexual-looking object, still dripping and nearly alive. I took it in my hand, tilted the shell back into my mouth as instructed by the by now beaming Monsieur Saint-Jour, and with one bite and a slurp, wolfed it down. It tasted seawater… of brine and flesh… and somehow… of the future. I’d not only survived – I’d enjoyed. This, I knew, was the magic I had until now only dimly and spitefully aware of. I was hooked. My parents’ shudders, my little brother’s expression of unrestrained revulsion and amazement only reinforced the sense that I had, somehow, become a man. I had had an adventure, tasted forbidden fruit, and everything that followed in my life – the food, the long and often stupid and self-destructive chase for the next thing, whether it was drugs or sex or some other new sensation – would all stem from this moment. I’d learned something. Viscerally, instinctively, spiritually – even in some precursive way, sexually – and there was no turning back. The genie was out of the bottle.

In my case, I was about twelve, celebrating a cousin’s 80th birthday in Scotland. The children of the cousin were all scheduled to come into town — all except the youngest, Bruce, whose arrival was meant to be a surprise. Bruce, being that kind of guy, wanted his brother to pick him up from the airport and take him to the dock, where he could then take a boat and sail around to the house where everyone was staying. Surprise!

I’ve forgotten what messed it up. Bad weather, probably. A missed flight or connection in France. He ended up flying into town in the middle of the night, his big surprise ruined, toting along an enormous duffle bag of fresh oysters that, no doubt, he had planned on hauling out with a victorious yawp just as he pulled the boat ashore.

Instead, when I came into the kitchen in my nightgown at 7 am the next morning, there was Bruce, an enormous, angry man, eating oysters out of a duffle bag, just shucking and shoveling, one after the other. They hadn’t been refrigerated, I guess, on the way over. They must have been a hell of an investment, and he was going to eat them if it killed him. He was drinking the champagne that must have gone with them, too.

“Do you want one?” he offered. But I shook my head no.

“You’re from the U.S.?” I shook my head yes.

“I know a guy from the U.S. Ted Turner. You know him?”

I didn’t, so I shook my head no.

“I was at a yacht competition1 with Ted Turner one New Years. Down in Tasmania. It was New Years, so we were all drunk, and someone spotted this woman on the dock in a tight dress — she was teasing every cock in the dock with that dress. And Ted Turner and his mates go down there and tackle her and he yells up to me — Bruce! I caught the Tasmanian Devil! So I called back, You might have caught her, but you haven’t *had* her yet!”

Bruce roared, and then continued shucking, shoveling.

Because that’s what we want from our oysters, isn’t it? An abundance of life, and then a simple latch, unlocking their simple death.

Not to get too Freudian on all of us but … snakes! I was kind of half-kidding about everyone loving snakes but I clearly did not fully comprehend how awesome of a community of readers y’all are.

Chris La Tray writes An Irritable Métis on the current political moment, Indigenous issues, and the natural world from his home in Montana. He sent this fantastic photo of a garter snake — I don’t think I’ve ever seen one as gorgeously colored or as elaborately patterned.

Chris is also the author of One Sentence Journal: Short Poems and Essays from the World At Large, which I’ve just received and am very much looking forward to reading. Thanks for the snake pic, Chris!

Reader & friend Cal wrote with a photo of a snake carving at a Hindu temple at Bali. I can’t find exactly the same one without a copyright, but this one — also in Bali — may have similar significance. Certainly, snakes have a powerful presence in religion and mythology.

And reader Jennifer M. wrote in with a picture of this lovely (and huge!) common water snake. Thanks so much!

Thanks to all, keep ‘em coming, and I hope y’all have a wanderful week.

How Bruce made his money was something I found out later, and might explore in a longer version of this essay.

Lovely writing as usual, from the disturbingly inappropriate cousin (that reminded me of my own childhood) to the oysters and middens. I visited a 1500 year old one on the shore of New Jersey. And my first raw oyster was with my father at a long gone seafood restaurant attached to a fishmonger's. You always remember it, don't you? Like Bourdain says. "it was a brave man who first ate an oyster," and maybe that's way. My mother prefers cherrystone clams, and I like those too. Those are lovely snake photos, and I'm glad more people appreciate them now. I learned to stop telling adults that I found a harmless snake the first time they killed it.

Oysters

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

Alive and violated,

They lay on their bed of ice:

Bivalves: the split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean

Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered.

We had driven to that coast

Through flowers and limestone

And there we were, toasting friendship,

Laying down a perfect memory

In the cool of thatch and crockery.

Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow,

The Romans hauled their oysters south of Rome:

I saw damp panniers disgorge

The frond-lipped, brine-stung

Glut of privilege

And was angry that my trust could not repose

In the clear light, like poetry or freedom

Leaning in from sea. I ate the day

Deliberately, that its tang

Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

Seamus Heaney