What are monsters?

I am sure there are dissertations written on this very topic, but I was just thinking about my personal fascination with the upcoming cicada emergence, and also thinking back on being engulfed in a storm of crickets in Kenya. I’ve mentioned this before, but when Michael and I visited Matthews Range in central Kenya in the summer of 2018, we witnessed the very start of what was to become a devastating plague of grasshoppers, spreading from Pakistan and India, down through Oman and Yemen, and then to the Horn of Africa.

Anything with four limbs seems OK (two legs and two wings seems to count). Walking, running, crawling, and ambling are the preferred modes of transportation; swimming can be alright too, but it’s iffy.

Flying away from us is magical; toward us or near us is terrifying.

Smallish, regular teeth in a nice, even jaw, two eyes and a nose: not a monster.

But if you start adding or subtracting to this formula: fewer limbs, bigger teeth, some weird way of moving, extra eyes: now you’re moving into monster territory. Now you’re getting scary.

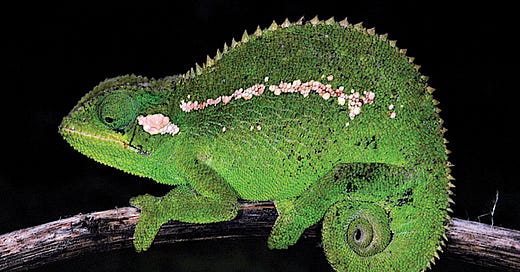

Scientists have recently described a new spiny chameleon species from the Bale Mountains of south-central Ethiopia, and it, no matter how odd it is, is not a monster.

Source: Living individual of Trioceros wolfgangboehmei sp. nov. from Dinsho, Ethiopia showing a prominent white temporal spot and dorsolateral longitudinal stripe. Photo by Petr Nečas. Part of: Koppetsch T, Nečas P, Wipfler B (2021) A new chameleon of the Trioceros affinis species complex (Squamata, Chamaeleonidae) from Ethiopia. Zoosystematics and Evolution 97(1): 161-179. https://doi.org/10.3897/zse.97.57297

I mean, yes, he could maybe do with some scale de-fungus cream (unless that’s just how his scales look?); and true, the daggers running down the back of his spine do look exactly how I drew dragons when I was about eight; and alright, yes, his eyes do swivel independently of each other as if he were at the tail end of a serious three-day bender … and yet I am almost 100% confident (and correct me in the comments if I’m wrong about this) that we can all say that this creature is no monster. I’d go so far as to say he’s cute? I would totally hold him if it were safe to do so.

I’m separated from my husband at the moment, but when we lived together, I kept a kosher kitchen, and while I never became kosher myself, I understood at least the part of it that seemed to be about avoiding monsters.

Is this animal that I’m about to eat a bottom feeder, does it live in the mud like a catfish? If yes, don’t eat it.

Does this pig, in the immortal words of Pulp Fiction, sleep in rue and shit? Obviously, don’t eat it.

Is it a blob of mucus, does it do nothing all day but filter out the pollutants from its surrounding area, does it live on refuse? Are you fucking kidding me?

I mean, I eat all these animals myself, sometimes guiltily, sometimes with no guilt at all — I eat mussels and clams and oysters and also pigs and catfish and so on, but I can see how you’d come to divide the world into monstrous animals and non-monstrous animals, and I can see how the circle of non-monsters might start shrinking, how once you get right down to it, lots of animals start looking pretty odd, and now that you mention it, lots of us seem to have a lot of defects too, lots of us are lame or blind or maybe just a little loud sometimes. Lots of us stand out. Lots of us are a little monstrous. And then what do you do about that?

Interestingly, the one kosher insect is the grasshopper, which en mass, becomes the locust. The insect doesn’t change, per se, but how perceive it does.

Or maybe the grasshopper does change when it becomes part of a swarm.

I have already mentioned one assignment I had, volunteering at the National Book Festival; another (and my absolute favorite) was being an “author escort” to Lisa Margonelli, the author of Underbug: An Obsessive Tale of Termites and Technology.

I do a lot of my reading before bed, so for about a week leading up to the book fair, I was reading the book, then dreaming about termites; when I met Margonelli, it turned out she dreamt all the time about termites. This, she declared, was “very termite” of us, sharing dreams like this. Maybe we were joining the hive somehow. Maybe just by thinking of them, we were becoming part of the larger termite organism: that thing made up of individuals, but that is more than just a group of individuals. Possibly, we had become part termite? Monsters, indeed.

I can see why it might be important to eat grasshoppers, which turn into locusts, which threaten crops and also, monstrously, threaten us.

How lucky we are in the United States, awaiting our cicadas! What a complete luck-of-the-draw, and yet somehow entirely-in-line-with-American-mythology coincidence, to end up with the derpiest plague imaginable.

Our plague does not bite! It does not consume our crops or bring disease. It emerges on a predictable timer, just a bunch of horny teenagers, intent on nothing but making noise and getting laid.

And we — we can sit back, enjoy our monsters, the world’s silliest plague.

“Here we come!” they say, bursting forth from their holes.

It’s time for cicada Mardi Gras! It’s time to turn the world on its head! Now we are small, but soon we will be larger than you. Now, we are individuals, but soon, we will join you, engulf you — soon, we will be monsters together.

This was a fun read! I love cicadas.