I am back in DC now. Last Friday night, the night before I left Blacksburg, where my Mom lives, I listened in on a webinar on cheetah ecology by Anne Hillborn.

I don’t know Anne Hilborn but I feel like I do, a little, from following her on Twitter. I suspect she has a penchant for naming some of the cheetahs she’s observing after liquor, like Amarula, a liquor made from the nuts of the amarula tree. I know she did her PhD research in a house built in the 60’s for the purpose of Serengeti research and that has been slowly crumbling around each successive generation of scientists ever since. And I know that the webinar was held on Singapore time. It was 10:30 am on Saturday in Singapore, 7:30 pm in San Francisco, and 10:30 pm in Blacksburg, Virginia, when I tuned in.

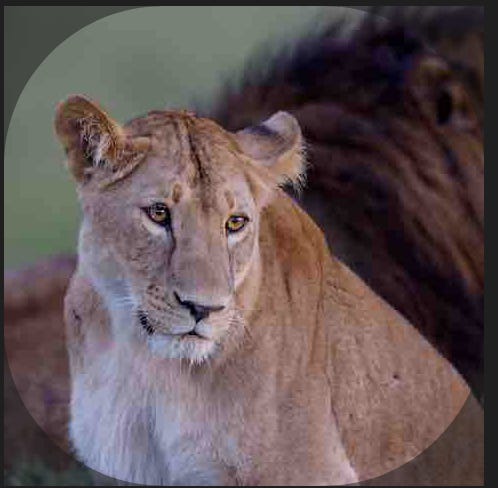

Most of us in attendance in the cheetah Zoom took the now-familiar avatar of rounded shoulders and blank, bald heads — light blue against a dark blue background. A few of us had selfies. I used a picture of a post-coital lion I took one particularly fine night in Kenya.

The original picture featured both male and female lion, juxtaposed and making an “x” of their bodies. He’s relaxed, or as relaxed as it’s possible to look in the middle of a test of sexual endurance and stamina. Over the next few days, they’ll mate hundreds of times, barely pausing, not eating, any moment of relief overcome and subsumed in the next moment of urgency.

In order to fit the square block you’re given for your avatar, I’ve edited out the male.

The female looks up, over the right shoulder of the camerawoman — me. The details in the picture are — if I do say myself — hard as nails, even zoomed in. You can see the light in her eyes — the horizon is reflected there, and something tall, a tree probably, towers on the horizon. You can see her ear tufts. She wrinkles the darker-tan patches above her eyes in an expression that looks to me like an expression of concern.

It’s impossible for me to tell, of course, if she wrinkles her brow to express concern. Facial expressions and their meanings hardly hold consistent across human cultures. To speculate across species is, no doubt, foolish in the extreme. And still, here I sit with these two lions. Along with her wrinkled brow, there’s something soft about her face, some long gaze. Is it satisfaction? Is it contentment? Is it some lion emotion I can’t imagine? Who knows?

I think of all my fellow audience members on this zoom call, what they must be doing, all around the world, while listening to this discussion of cheetah behavior. What they must be thinking, feeling.

Personally, I’ve finally gotten up the energy to scoot off the big bed in the upstairs guest bedroom. I’m brushing my teeth, I’m taking my pills, I’m learning about cheetahs, and my lioness is shielding me. No one can see me, all they see is the worried lioness.

Lionesses have many concerns, but among all her other worries, lions have spines on their penises that point backwards, making it more difficult for her to escape after mating has started. Possibly the raking helps to start ovulation? That’s the theory anyway. I think it’s more like those spikes at rental car companies, the ones with the signs warning you, “DO NOT BACK UP.”

I’m anxious myself. My mom is asleep, one floor below me. She’s had one eye surgery, she’ll have another in a few weeks.

What is everyone else doing? Has someone woken up in France just to hear this? Are they drinking good coffee, eating their yogurt, about to start their Saturday?

Dennis Minja, the current project manager of the Serengeti Cheetah Project (who is about to start his PhD work, the same path as Anne followed before him), introduced Anne Hilborn, presumably from Kenya. The Singapore Wildcat Action Group sponsored the talk and hosted the Q&A — for them, this was an evening discussion.

I felt our own social structures swirl and eddy around us. It was impossible to know what was going on with each of us, we were having such wildly different experiences, eating different meals, at various stages of dress or undress, at various moments in the sleep/wake cycle; and yet we also shared an experience, we could be together in some sense at one imaginary time, though the time itself differed for each of us.

According to Hilborn, cheetahs have a unique social structure among cats. She writes:

Instead of having territories like other species, female cheetahs instead roam widely following the gazelle migration.

Males can be either solitary or in coalitions with other males, and either territorial or nomadic.

Females are solitary except when they have cubs, which they keep with them for about 18 months. After independence from their mother, siblings stay together for 6 months, then the sisters will strike out on their own while brothers will form lifelong coalitions. Adolescence is a socially flexible time. Males without brothers will sometimes find another and form a coalition.

In her research, she got particularly interested in whether the territorial or nomadic males sired more cubs. If the territorial, did the size of territory matter? The answer, it turned out was yes, and also yes, and more yes.

Cheetah moms are, in Hilborn’s words, “a little promiscuous.” When they looked at the poop of a whole bunch of cheetahs, they found that multiple male cheetahs often sired cheetahs in a single litter. This, presumably, discouraged male cheetahs from killing a litter of cubs — something male lions are famous for.

A picture of Anne Hilborn’s webinar and the slide on a single litter of cubs sired by multiple fathers.

I don’t have any pictures of cheetahs doing what they’re most known for: running. In fact, I’ve never seen a hunt, something I might write about in another entry.

But one misty morning in Kenya, my guides told me that they were going out to find a new cheetah mom. They knew she was pregnant and had heard she had given birth in an area with many low bushes. Once she was found, they would call the rangers, and the rangers would close the area to give her privacy to raise her cubs for a few weeks. Did I want to come along to help identify her den?

Did I?

I can’t seem to stop looking at pictures of moms and moms-to-be in these cat pictures. I can’t seem to stop imagining the lives they live, their very different social structures.

I can’t seem to stop thinking about how we’re changing our social structure, at a warp speed that would have been hard to imagine, pre-pandemic, forging new and different kinds of connections across the globe.

Our lives might never touch again, but they’ve touched here, this night, when I worried about my mom, and I looked like a concerned post-coital lion and you looked like a light-blue blob.

My mom had eye surgery, you may have lost a job, or had a birthday, or gotten engaged. We’ve both learned something new about cheetahs. Something was affirmed, and then, like the flickering spots of a cheetah racing past us, was gone.

***

I can’t sign off without saying thanks to two friends.

First, Jennifer, librarian-extraordinaire, for finding the Dudley Cemetery from my last post. Apparently, it’s a family cemetery and the graves circle a single tree, which is why I can’t see them as I drive by.

Jennifer, your investigatory skills never cease to amaze.

And second, Anne-Louise, whose brilliant paintings of cheetahs kept me company in my mind’s eye as I wrote this.

Wishing you all a wonderful week with many meaningful contacts: old-fashioned, newfangled, roaring, barking, talking, purring, and otherwise.

🙏💛 much love to you, Hannah

Your posts are always so interesting.