On Being Brickish

One of my favorite advice writers, Heather Havrilesky, wrote this week about being a brick. Sometimes I think I should report her to the FBI for spying on me, or that she’s my secret girlfriend, or maybe she’s an alien connected to the UFOs that the Pentagon’s been getting all hot about lately.

However she found out about my feeling like a brick, this is what she writes about it:

I thought I would feel settled and satisfied once everyone in my family was vaccinated. I thought I would feel energetic and thrilled to be alive. And some part of me feels like THAT’S HOW I SHOULD FEEL.

But nothing makes you feel like more of a brick than trying to feel something that you don’t feel. So now you’re not just a brick, you’re A GUILTY BRICK. And how do you help your brick friends when you’re also a brick? Suddenly you’re not just a guilty brick, you’re a disappointing, pointless, ungrateful brick, too.

No doubt, having a sprained ankle contributes to my brickiness, so yesterday, I took my brick self and heaved it into the water via a kayak.

I’ve only kayaked a couple of times, and now that I look back, it’s always been in a tandem boat (with one other person in the boat).

A kayak, more than most other vessels I’ve been in, feels exactly like a small hole in the water that you happen to sit in. It feels like setting yourself adrift in a cartoonishly long shoe, as if you were a character from Mother Goose, possibly with a nose so long it grows to meet the end of the boat, or with a tail that steers the boat, or, probably, both.

At first, particularly when you are a brick, it feels impossible that you will float in this thing. I thought I would sink right there at the dock, with the impossibly tanned, toned, & relaxed college kids who rent out the boats for the summer looking on.

“Never seen that before, Joe, have you?”

“Nope.” [Pause]

“The four o’clock reservations are here — Sue, you get the canoe.”

Somehow or another, I didn’t tip in the first minute. I paddled a little. Another minute passed. I paddled out past the mud flats where the docks are sheltered, and the Potomac stretched in front of me.

Families were picnicking along the banks of the river; some were fishing. A cormorant flew by me at eye level, its neck unfurled like some black javelin, its color melty like fresh tar in summer.

I wondered if I could cross the river. Not very easily, as it turned out.

If I knew anything at all about kayaking, it was from taking a few trips out in the calm ocean waters between islands in British Columbia. There, the water was almost as placid as a lake — at least when we went out — but bejeweled with saltwater treasures.

I was particularly enamored of the starfish, who seemed to clump together with no sense of personal space at all, no interest in thinking, “you know what, if they’re all hunting over there, then I’ll hunt over here and not have to share.” No, they were all about sharing: food, limbs, space, oxygen, you name it, they seemed to share it, and all in the most dazzling colors too.

This experience gave me, perhaps, a false sense of security, so that the first time I went kayaking in the Potomac — this was several years ago — and experiencing its (I’m sure very mild) current I and my boat-companion ended up in the drink.

Long-time DC residents, remembering the times when the Potomac practically glowed with pollution, avoided me for weeks, positive that I would shortly turn green or develop purple bumps. None of that happened, fortunately, but it has taken me a while to return to the Potomac and ask the white guys with dreds at the rental shack to hand over a kayak.

Now, I began to play, very lightly, with going upstream, and then floating back downstream. I couldn’t cross the river directly, but possibly I could if I allowed myself to be swept along in that direction. I noticed a woman who had found a quiet cove for herself and her paddle board, and who was now sitting on the paddle board for all the world like she would at a seat at Starbucks — now playing with her phone, now reading a book. I couldn’t imagine having her confidence, but I could take note of what a peaceful spot of water looked like, and try to find a place of my own.

I had stuck my phone in a ziplock baggie, and then put the baggie in a zippered pocket of my pants. Once I started kayaking, however, I realized how completely insane the idea was of rocking the boat in any way, for any reason. Only at the very end of my adventure did I extract my phone — cursing myself the entire way, sure I was making a mistake I would rue — to take just a few pictures through the plastic bag.

Several pictures were of a great blue heron that were so impressionistic that your mental picture of the bird, however hazy, is likely more accurate. But this is what it looked like, to be a brick, floating in a river yesterday.

Kayaking did not cure me of my brickiness, and I was not looking for a cure. I find it’s OK to be sad, to be incurably angry and upset and a brick sometimes. Even at my bricky worst, I can stay afloat, even if barely, in this weird hole in the water, this inflatable clown shoe that gets me eye level to a cormorant.

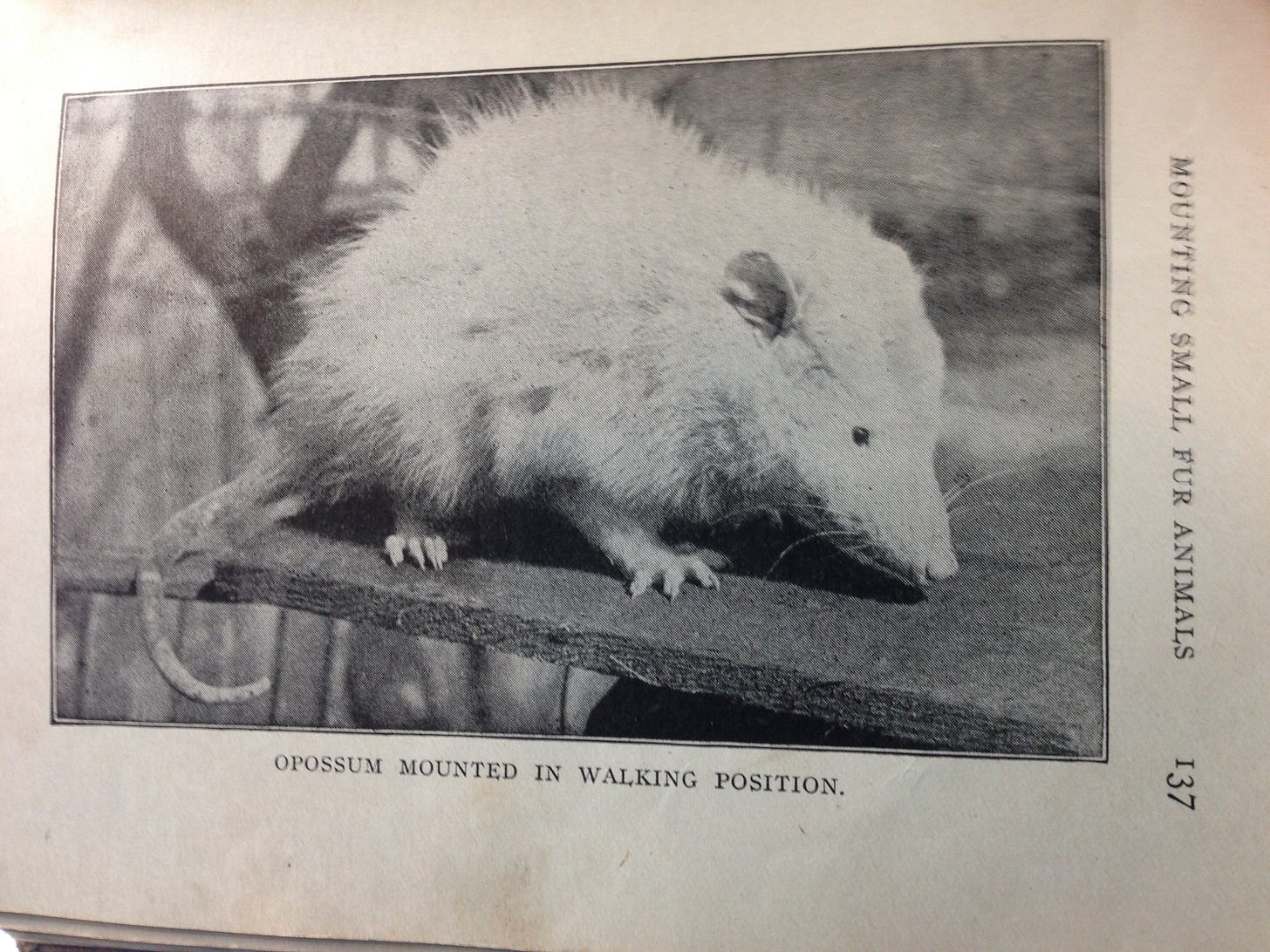

As a side note, while going through photos to find the British Colombia kayaking photos, I stumbled across these photos I took, also in B.C., of Home Taxidermy for Pleasure and Profit. I have no memory whatsoever of this book’s existence, but if it was for sale and I didn’t purchase it, honestly, I deserve whatever brickiness I am now experiencing and then some.

Another side note: I really enjoyed this article, “Grizzled,” by David Gessner, on an intra-environmental fight over a hiking trail (pull quote: “Not a fracking boom or a uranium mine or a new condo development, but a hiking trail. A hiking trail. We had met our enemy and they were us.”), and you might too.